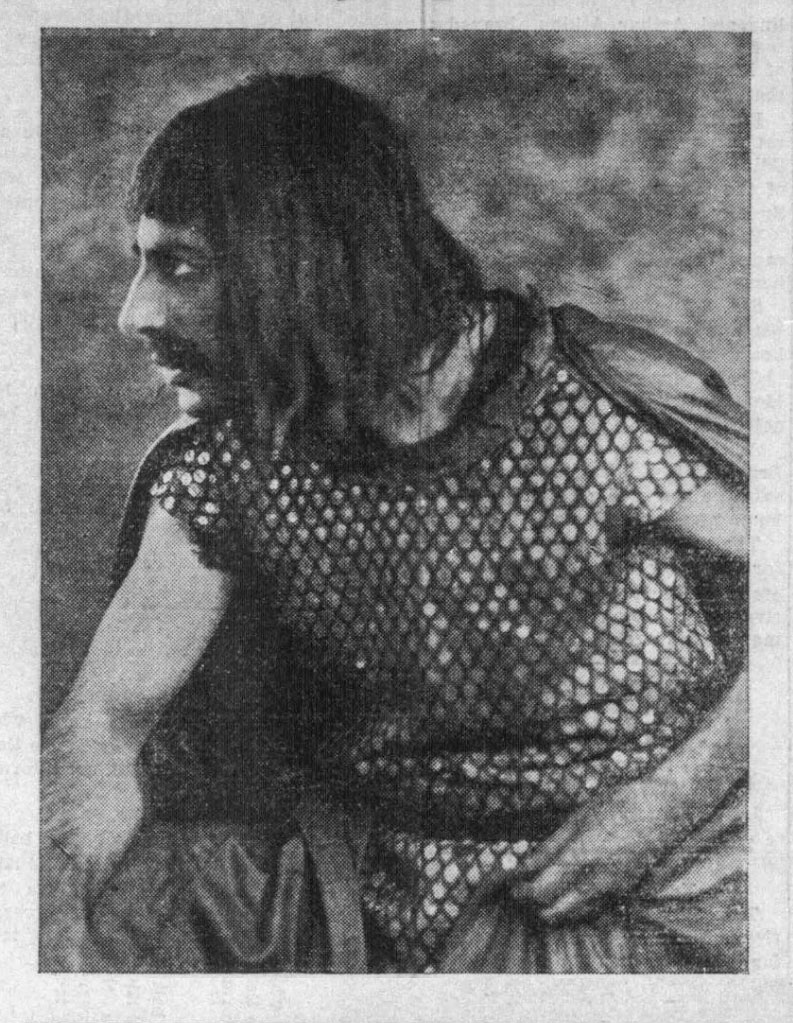

Leo Wyatt (1909–1981), engraver, lecturer, teacher.

Leo Wyatt led a life marked by hard knocks and hard work, lightened immeasurably by the devotion of his wife, support of his friends and, finally, America’s appreciation of his gifts. His career began in the relatively constricted centuries-old confines of commercial engravers, but he came into his own, inspired by Edward Johnston’s calligraphy revival and especially the work of John Howard Benson, Paul Standard and Reynolds Stone.

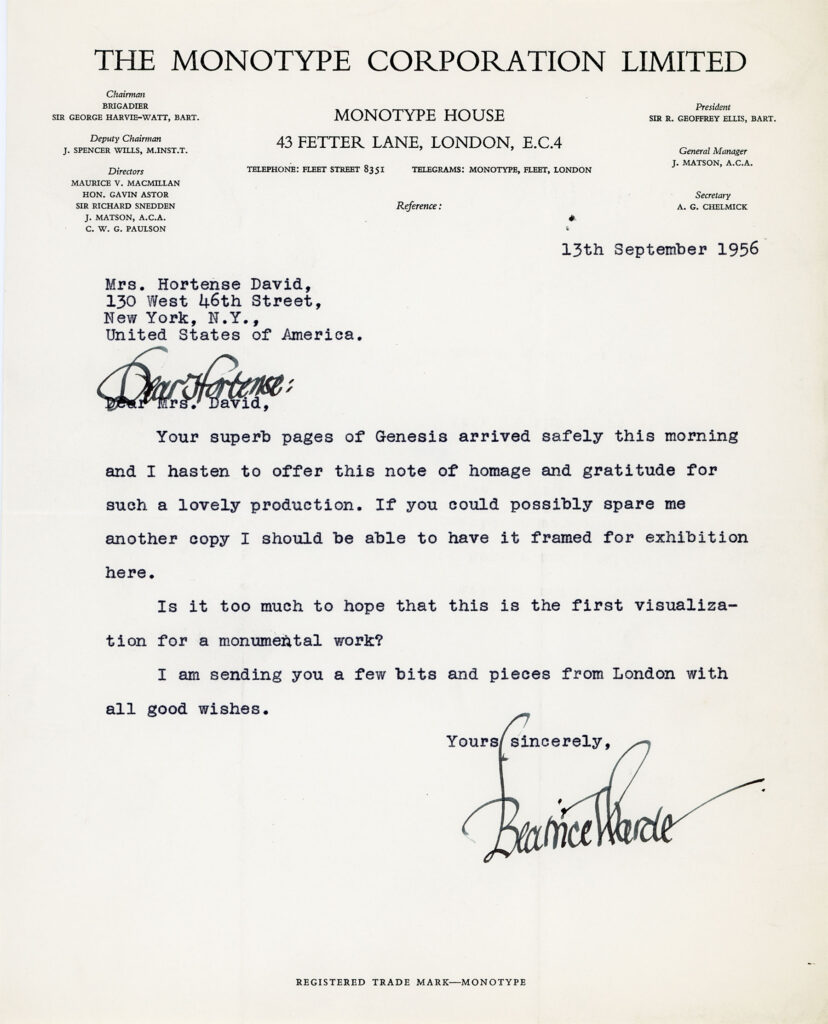

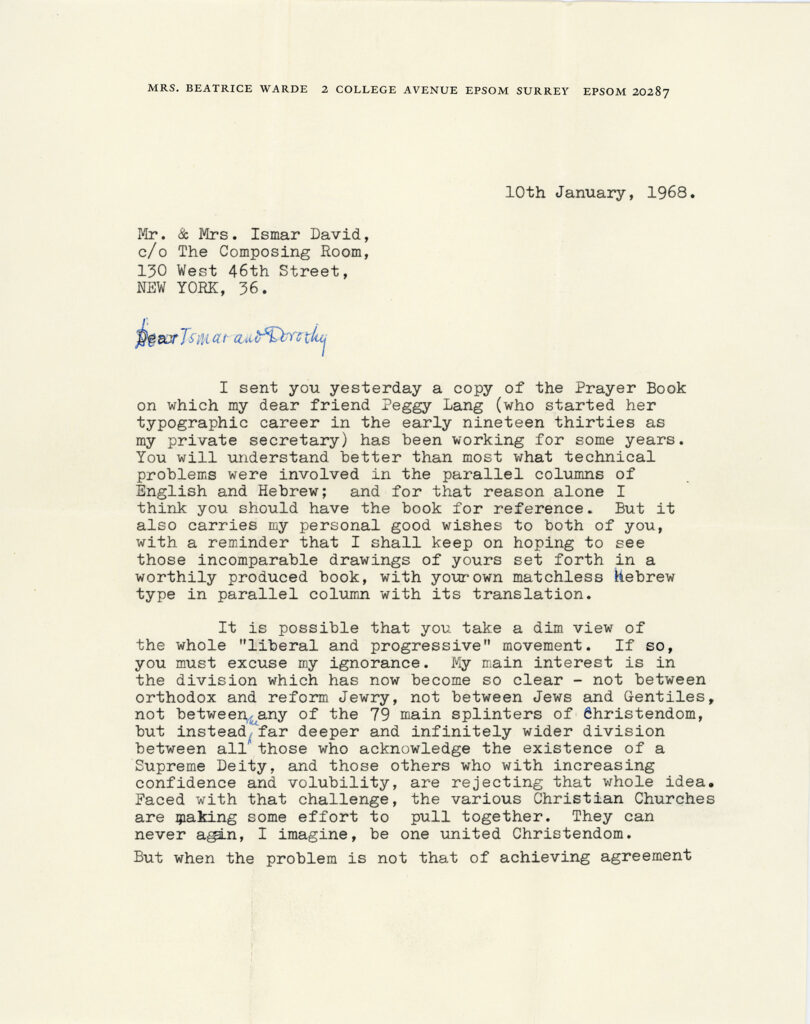

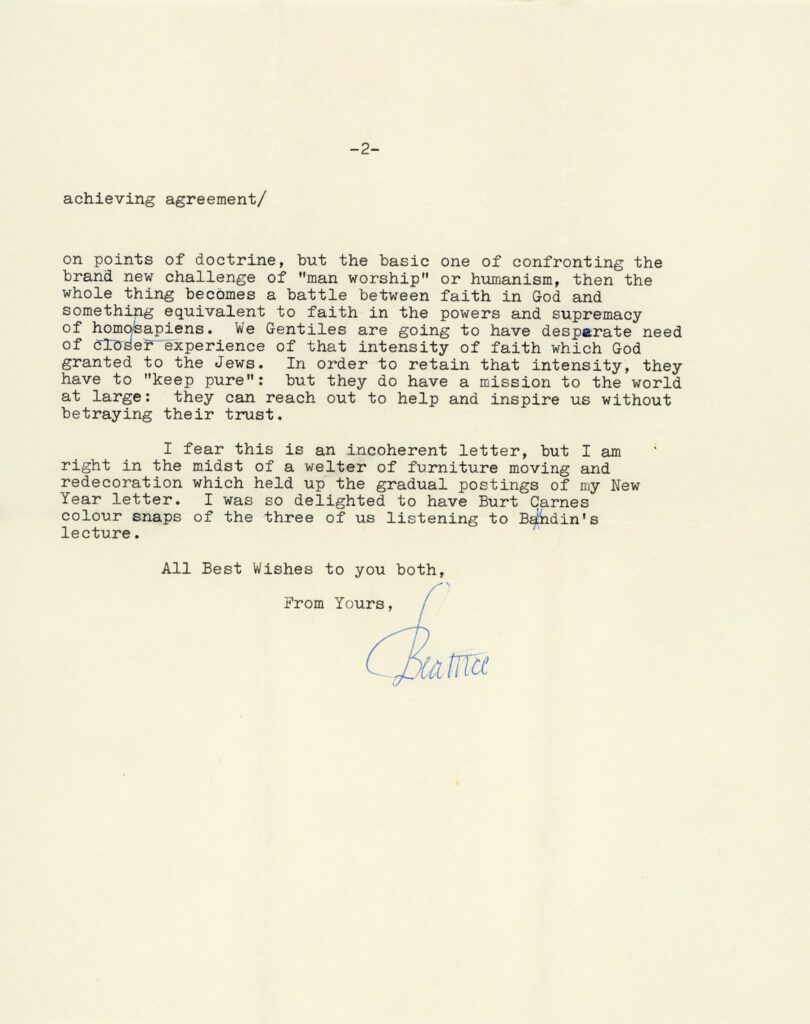

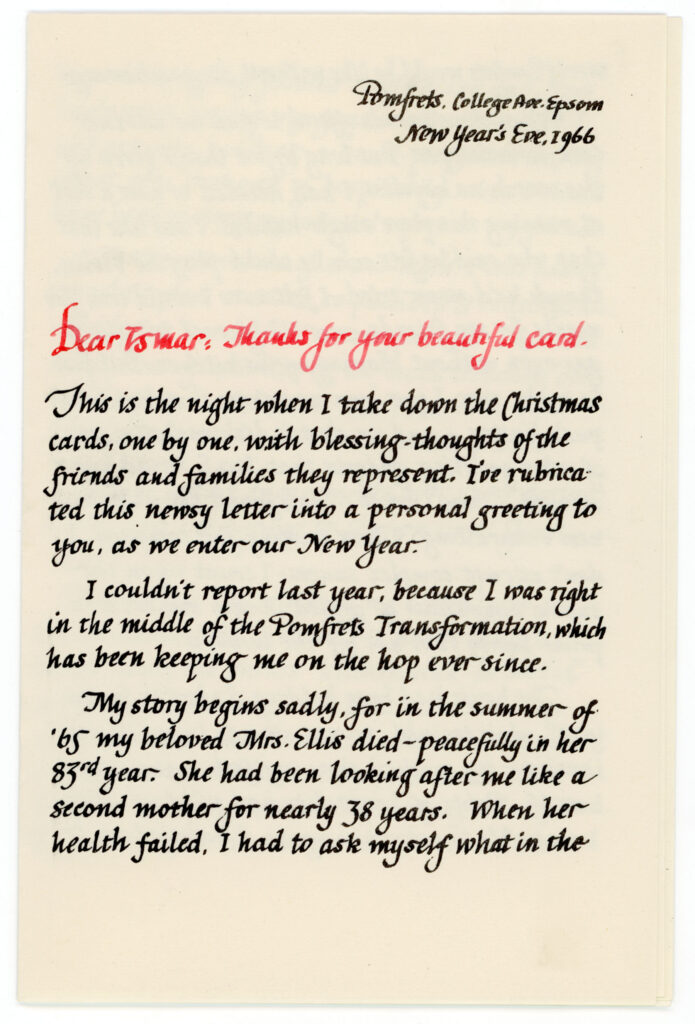

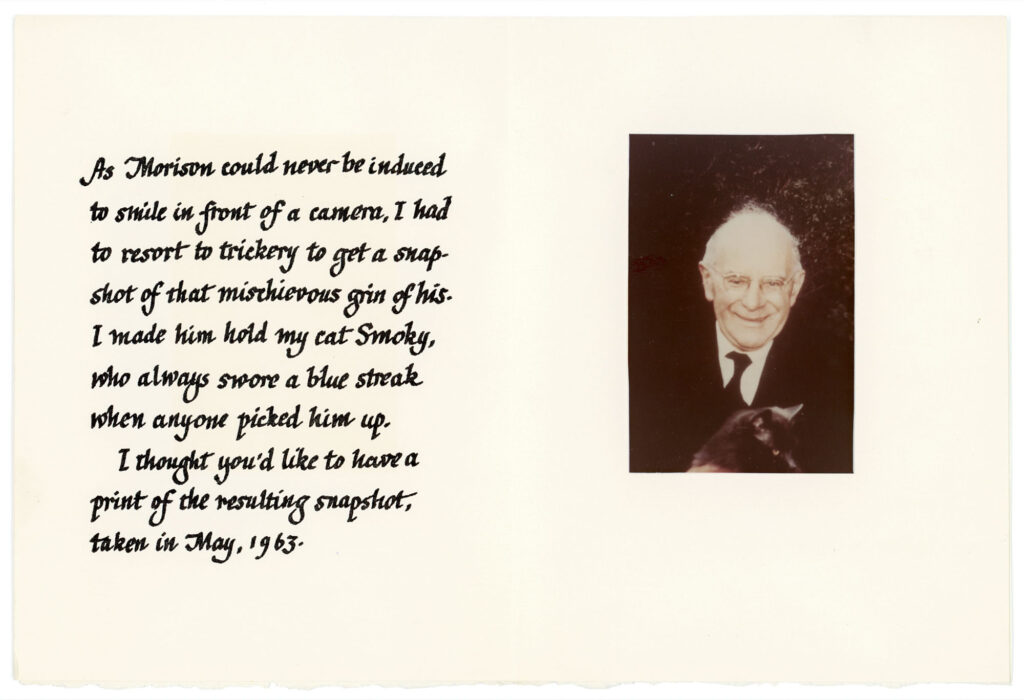

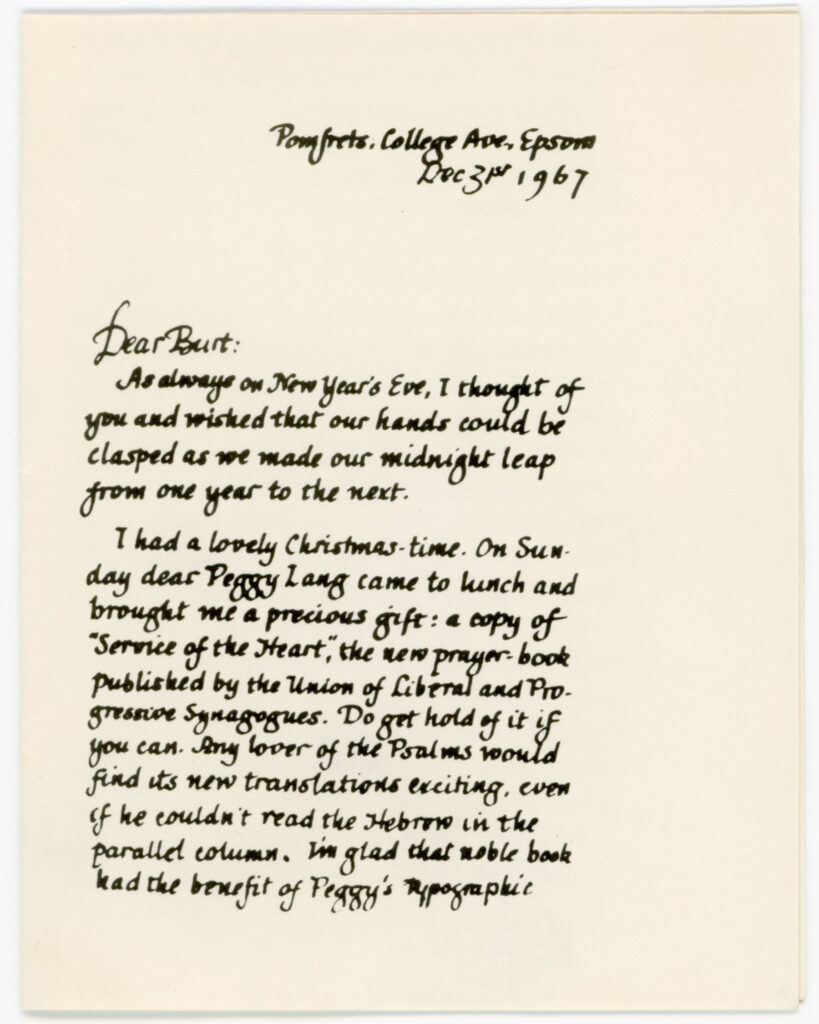

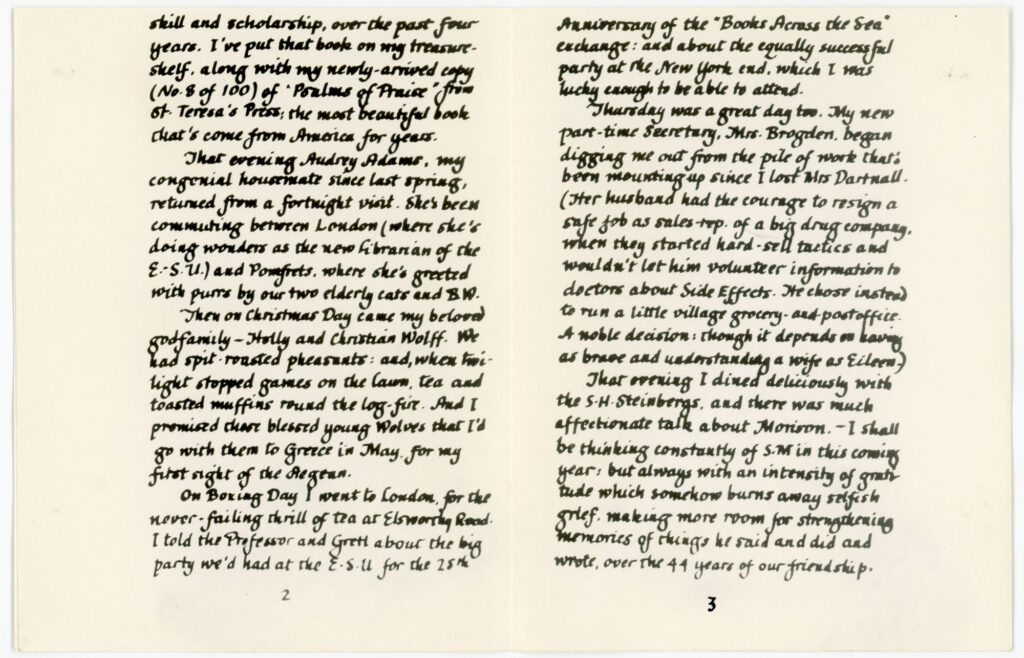

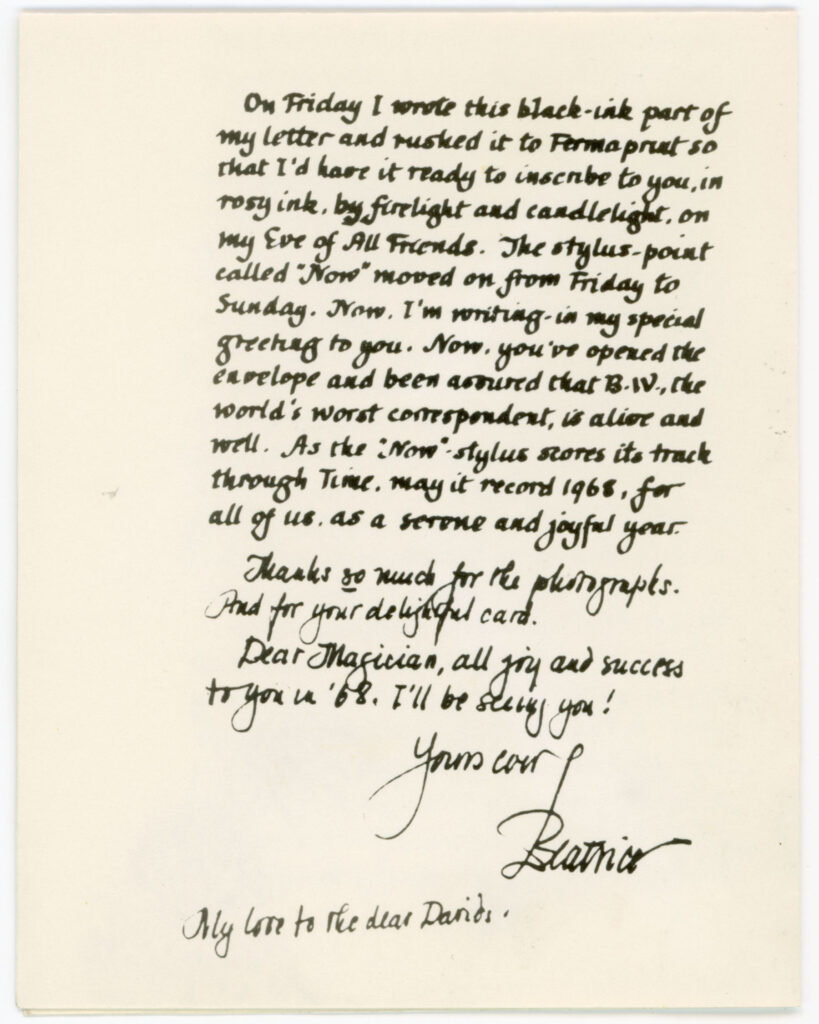

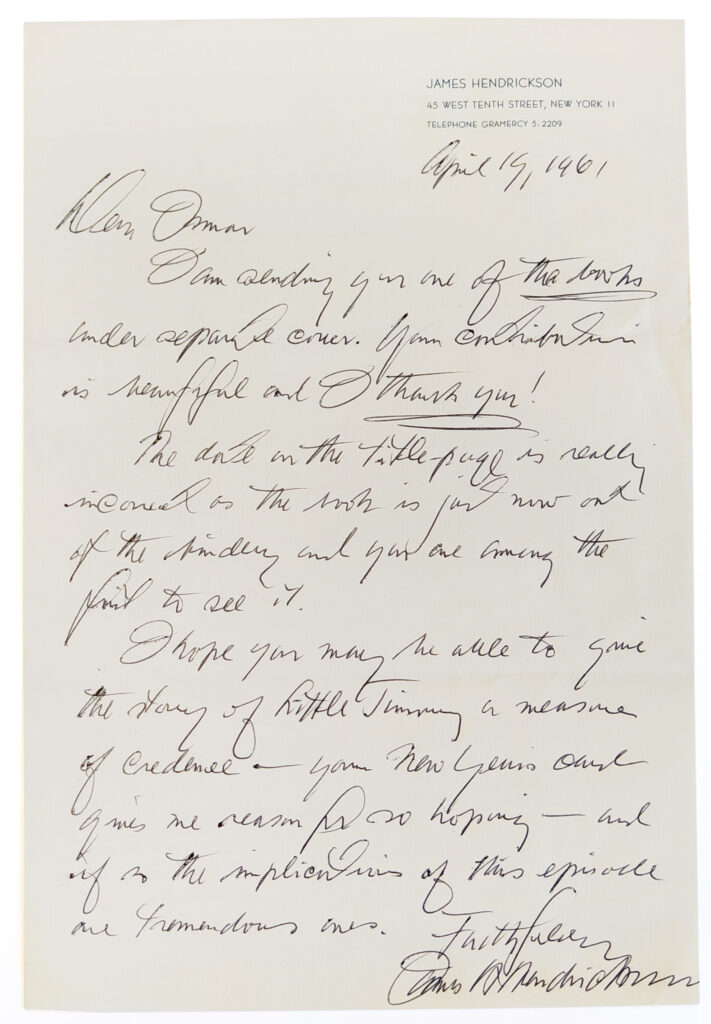

Removal to an orphanage at age 3 because his widowed mother could not afford to keep him suggests a Dickensian childhood, but Wyatt developed a good relationship with the headmaster in his new home and retained an affection for his somewhat feckless surviving parent. He was fourteen, when West End commercial engraver Dacier Baxter took him on as an apprentice for five years. Concurrently, he attended evening classes at London’s Central School of Arts and Crafts on scholarship. Despite winning Goldsmiths’, Silversmiths’ and Jewelers’ Art Council competitions in 1927, 1928, and 1929, Wyatt was plagued by chronic doubt. He spent much of the pre-World War II years knocking about Great Britain, working (or not) in London, Leeds, Edinburgh and finally, Bristol.1Lee, Brian North, Bookplates and labels by Leo Wyatt, introduced by Will Carter. Netherton, Wakefield, West Yorkshire : Fleece Press, 1988. Most of the above information and some at the end comes from this profile. In 1947, he and his family emigrated to South Africa, where he had “a very stimulating experience as the usual specialization that occurs in Europe does not exist [in South Africa]. That means that I have been tackling work usually carried out by half-a-dozen or so experts in their own spheres.”2“Back to Bristol,” Evening Post [Bristol, Avon, England], October 12, 1961, p. 31. Nevertheless, things were not easy. In 1952, he met “a kindred spirit,” Beatrice Warde, who was on a lecture tour. She “made it clear that she considered me capable of cutting first-class lettering and, from such a person, this was praise indeed.”3Ibid. Lee, Bookplates and labels by Leo Wyatt, p. 31. The family returned to England in 1961, only to face a fresh round of health and financial problems. Beatrice Warde stepped in to recommend Wyatt for a position at Newcastle Polytechnic. Despite having no prior experience, he became a fine teacher and beloved mentor.

The steady income gave him more time to devote to the sort of work he wanted to do: bookplates and wood-engraved lettering. His work was discovered by American collectors and the public. (Rollo and Alice Silver gave him his first commission in the United States.4Ibid. Lee, Bookplates and labels by Leo Wyatt, p. 49.) His fans spread the word for him and he lectured widely across the United States, making the later years of his life extraordinarily fruitful and rewarding.

John Dreyfus eulogized Wyatt:

“He always sold himself short. He could perceive talents in others but seemed desperately to under-rate his own. His reputation will take care of itself. His superb craftsmanship, his high principles, will ensure him a permanent place in the history of his craft and a lasting affection in the hearts of those that knew him.” 5Ibid. Lee, Bookplates and labels by Leo Wyatt, p. 50.