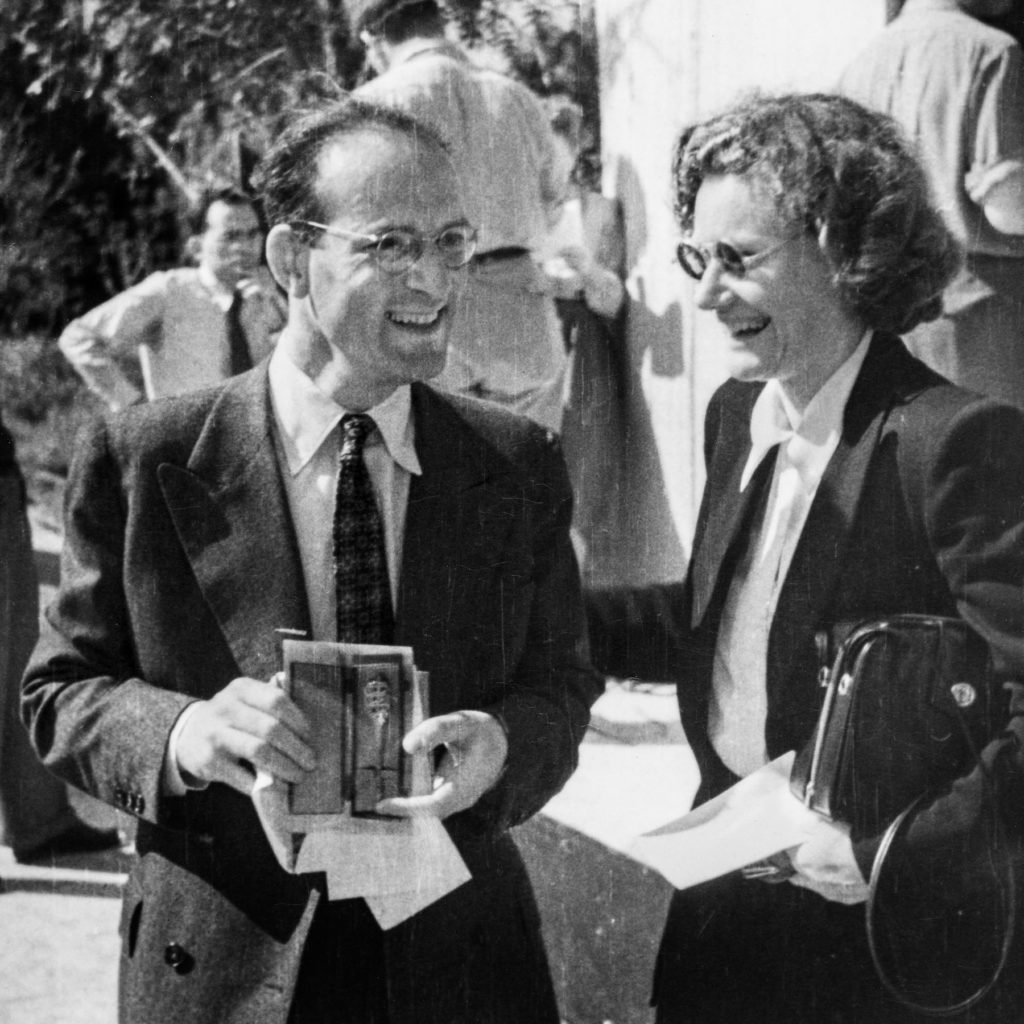

James Hendrickson, born c. 1898, actor-manager, typographer, printer.

“When I couldn’t decide which road to take, I decided to travel both,”1McCarthy, Julia, “Hamlet in Wintertime Is Printer in Summer,” The Daily News, June 20, 1938, p. p7. James Hendrickson told a reporter. And, a gratuitously snarky report in the New York Times notwithstanding,2Crisler, Ben, “Hamlet Hops the 6:45: James Hendrickson, Actor and Master Printer, Is One Who Knows a Hawk From a Handpress,” New York Times, July 22, 1934, sect. 9, p. 1. he did just that. Hendrickson (with his old-school repertory company, The Shakespeare Players) did “a world of good in keeping alive throughout the country the traditions of the legitimate stage through their interpretation of the works of the master dramatist.”3“Shakespeare Still Has Strong Appeal,” Plattsburgh Daily Press, October 28, 1933, p.4 And, when not on the road (from October to May), Hendrickson worked for and alongside some of the finest printers in America.

Hendrickson began printing as a kid. He bought his first equipment for $5 and set it up in his mother’s kitchen, making flyers for local shops. As the presses got bigger, the size of the kitchen unfortunately remained the same. “My bedroom, right over the kitchen, was my composing room. I would rush down the stairs with a chase full of type to the press room, where my mother was trying to bake pies. I had to dash upstairs again to make corrections. Back and forth, back and forth. Figure the excitement when I printed a 100-page cookbook.”4McCarthy, Julia, The Daily News, June 20, 1938, p. p7. Hendrickson was among the young printers who “apprenticed”5Loxley, Simon, “Frederic Warde, Crosby Gaige, and the Watch Hill Press,” Printing History, Summer 2008. at the prestigious press of William Edwin Rudge. He went on to succeed Frederick Warde at Crosby Gaige’s Watch Hill Press and was, for a few years, in charge of production at Alfred A. Knopf.6Bluementhal, Joseph, Typographic years : a printer’s journey through a half century, 1925-1975, printed for the members of the Grolier Club, 1982, p.79. In 1943, Hendrickson performed an invaluable service to printing history with his Paragraphs on Printing. Elicited from conversations with Bruce Rogers, as the subtitle explains, it is the only lengthy compilation of the design philosophy of a designer famously reticent to give it. When Joseph Blumenthal established a printing workshop for the AIGA in 1948, the shop director was Hendrickson.7Bluementhal, Typographic years, p.79.

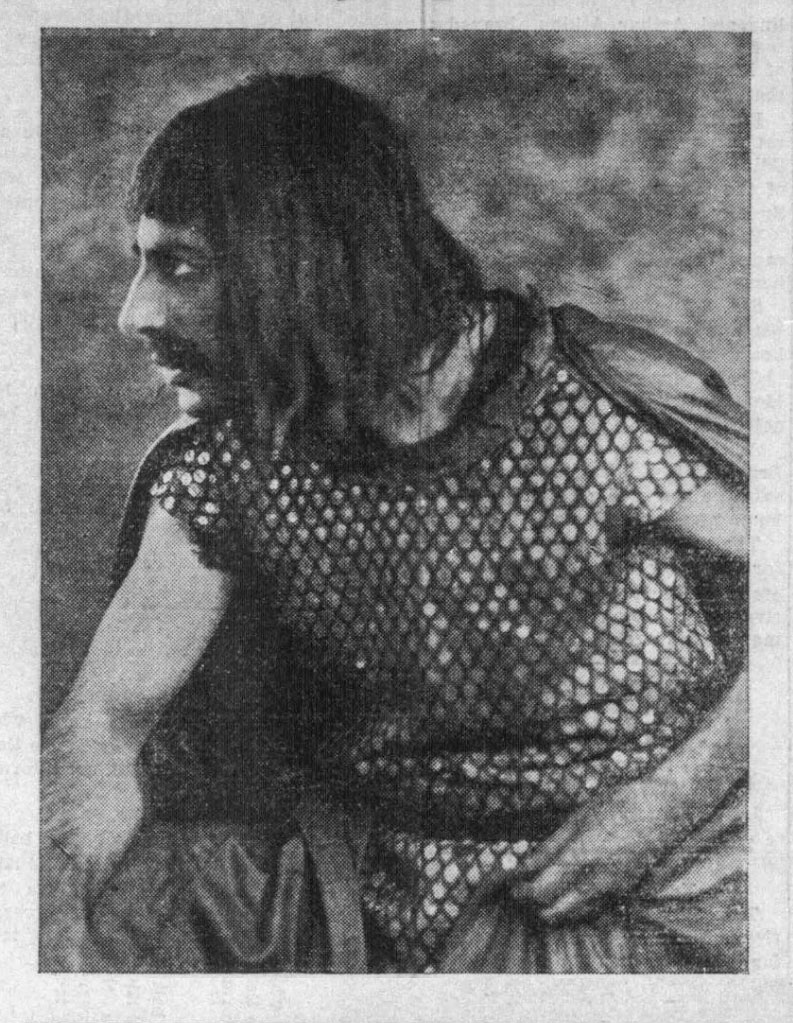

But the stage was irresistible and Hendrickson ambitious. No less than film star William Powell had encouraged him to be an actor, back when both were members of a Shakespeare Club in Kansas.8McCarthy, The Daily News, June 20, 1938, p. p7. This led to acting school after the First World War, then a decade as a journeyman performer, including two years traveling with Fritz Lieber and his troupe. In 1927, Hendrickson founded his own touring company with his wife, Claire Bruce, herself a veteran of a company lead by Robert B. Mantell. She played Ophelia to Hendrickson’s Hamlet and Lady Macbeth to his Scottish thane as they barnstormed colleges and high school auditoriums by bus, enduring all manner of catastrophe due to weather and road conditions.9“Shakespeare Cast Has Bus Accident; Cancels Date Here,” The Evening Times [Sayre Pennsylvania], February 9, 1935, p. 5. After the couple disbanded the Players in 1942, they ran a printing and design service out of their hotel apartment.10“Claire Bruce, Artist and Actress, Was 63,” The New York Times, April 6, 1959, p.27.

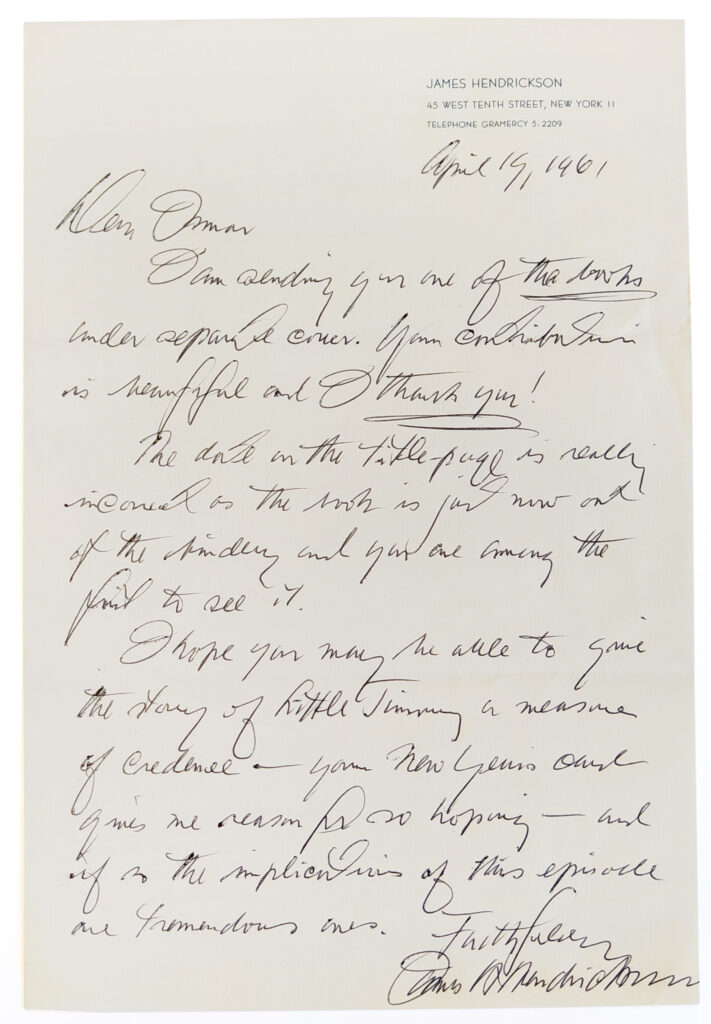

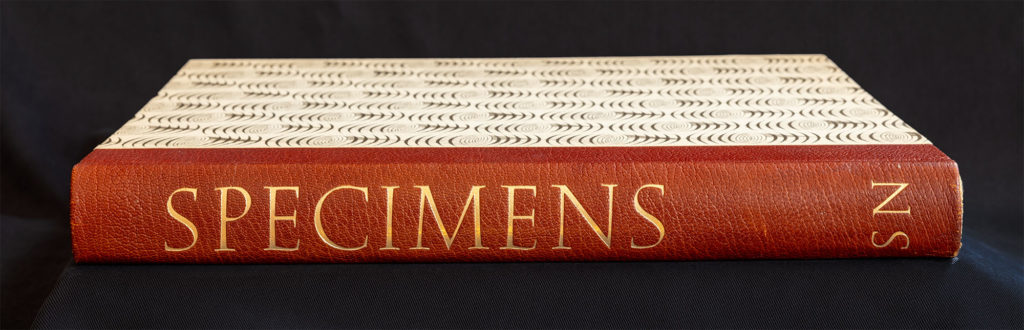

Claire Bruce died of a heart attack in April of 1959. A year later, Hendrickson printed an unusual tribute volume. It contains a reproduction of a spirit, or automatic, drawing. In this case, it is a colored-pencil sketch, depicting Sister Mary Cecilia holding little James Francis Weiss, “by Claire Bruce Hendrickson through the mediumship of Lillian Dee Johnson” in a totally darkened séance room on August 3, 1959. Ismar David did the lettering for the binding. When the book was finished in the spring of 1961, Hendrickson sent David a copy. In his note, Hendrickson refers to David’s most recent New Year’s card, which indirectly acknowledged the recent death of Hortense Mendel.

April 19, 1961

Dear Ismar

I am sending you one of the books under separate cover. Your contribution is beautiful and I thank you!

The date on the title page is really incorrect as the book is just now out of the bindery and you are among the first to see it.

I hope you may be able to give the story of Little Jimmy a measure of credence—your New Years card gives me reason for so hoping—and if so the implications of this episode are tremendous ones.

Faithfully,

James Hendrickson