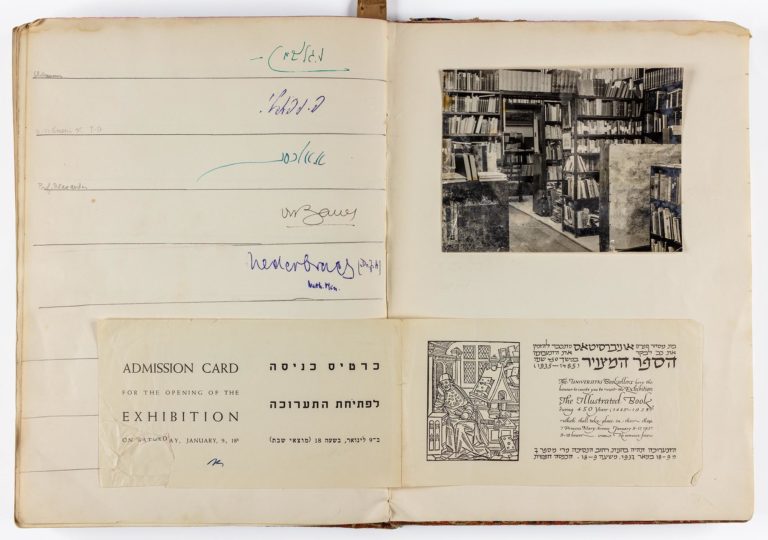

When the United Nations adopted its Partition Plan for Palestine on November 29, 1947, designer Ismar David was studying printing methods in New York. Some contemporary observers believed that Jerusalem would remain exempt from open hostilities, but sporadic fighting broke out in the city almost immediately. David cut short his intended 10-week stay in America to return to Jerusalem, landing at Lydda Airport on January 12, 1948.

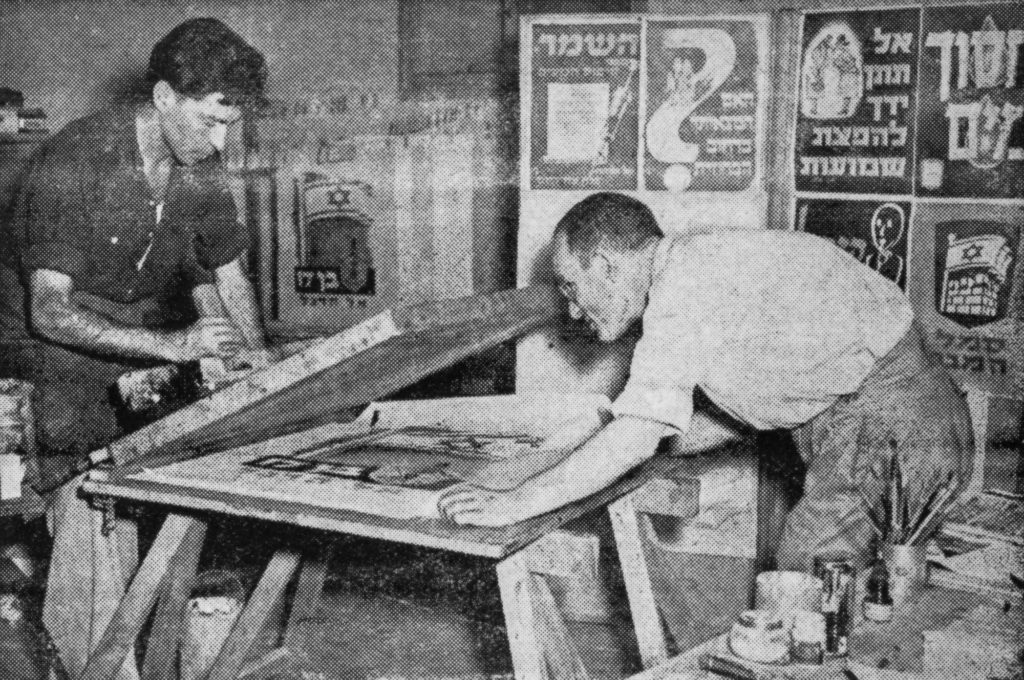

The escalating situation in Jerusalem demanded an efficient means of communicating with a multilingual populace and of galvanizing public sentiment and so, the Haganah organized a graphic department with David at its head. Twenty-five-year-old Yossi Stern, a freshly-baked Bezalel graduate and winner of its Hermann Struck Prize for Outstanding Student, Tel Aviv-based Emmanuel Grau, Eliyahu Price, and Gabriella Rosenthal filled out the rest of the team. Working out of David’s studio on Keren Kayemet Street, the group produced designs for stamps, stationery, maps, various periodicals and interior spaces, all at an astounding pace and while attending to their own civilian defense obligations.

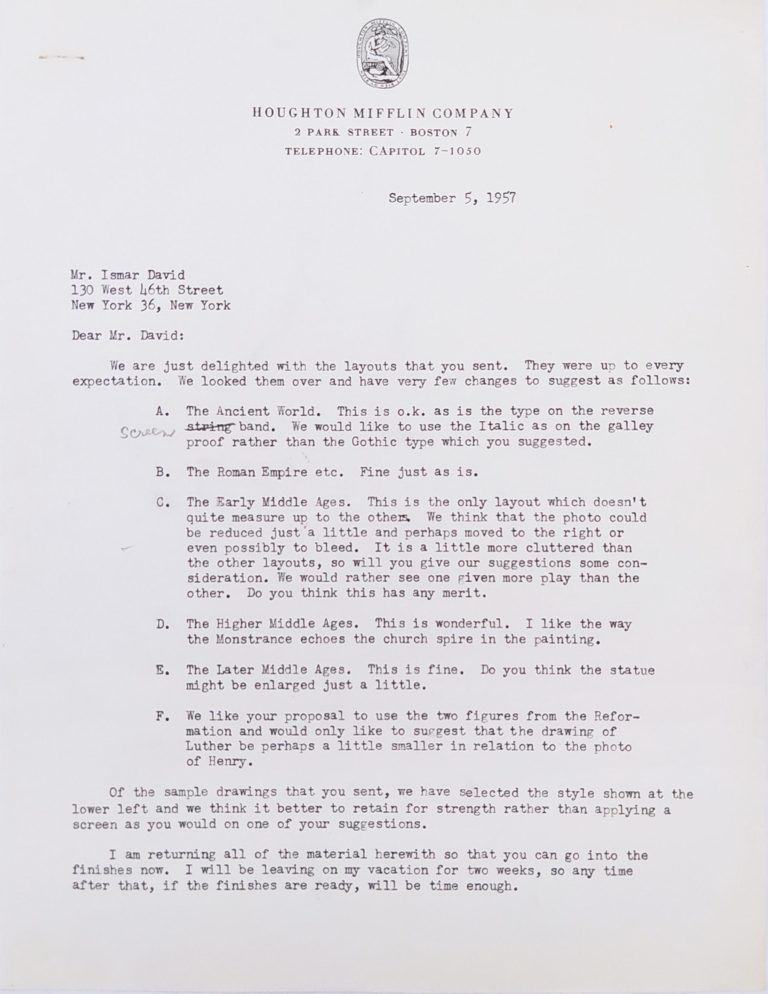

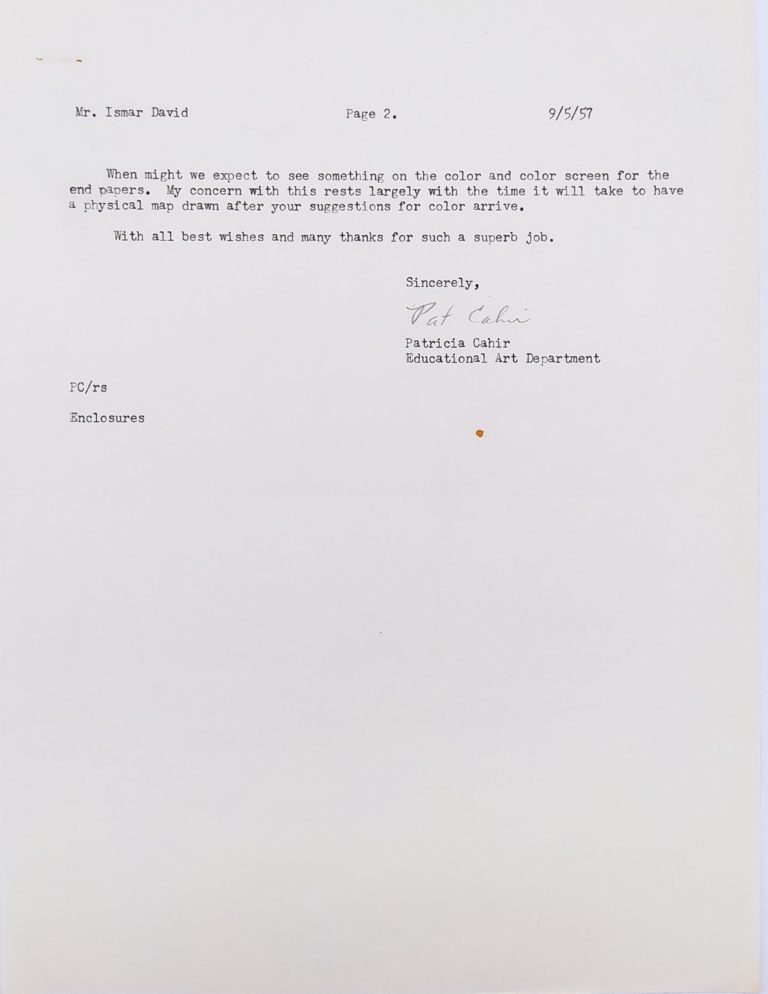

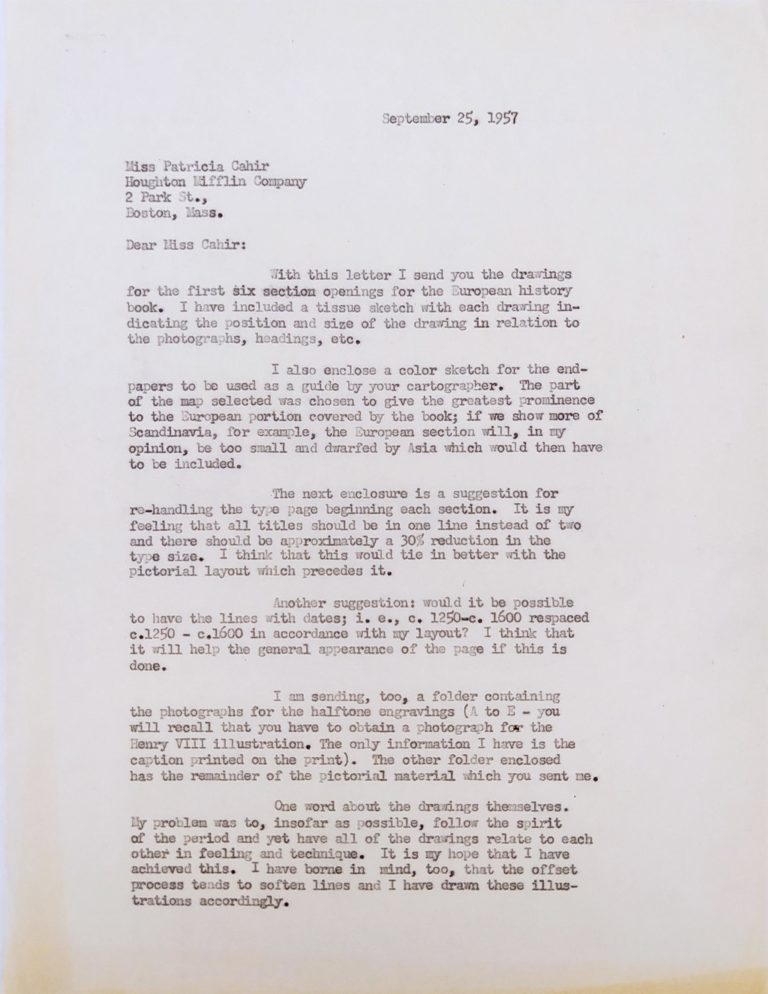

David designed a graphic identity for the Haganah, a blue shield with the Israeli flag waving above the ramparts of Jerusalem, and used this bold, new emblem as the focal point for the first of a series of posters, printed on paper shipped from America with the help of Helen Rossi and her sister Zelda Popkin.1Both Molly Abramowitz and Jeremy Popkin credit the sisters with helping to import the paper. Posters that followed, for the Haganah and for its affiliates, like the Mishmar ha-Am (People’s Guard), covered admonitions to be careful or to keep calm (with an illustration by Stern), and the perils of curiosity or spreading rumors (both with Stern’s illustrations). David’s water poster graphically distilled—in two water drops—the city’s dire need for conservation and the vulnerability of the Ras-el-Ain pipeline, which was, in fact, damaged by a mine on April 8, 1948.

Most of these works were printed on the only offset press in town, newly installed at A.L. Monsohn Lithographic Press in the Old City. The Haganah had to grant leave to Shimon Baramatz, grandson of the founder and only trained offset operator, to work the press.2 Abramowitz, Molly, The Mysterious Case of the Haganah Posters, Na’amat Woman, summer 2009, p. 15 When combat or lack of electricity made offset impossible, David used a silk screen setup in his studio. A series of silk-screened Biblical quotations, often printed on the verso of earlier posters, were doubtless meant to strengthen resolve at a time when morale was likely even lower than the supply of paper.

The siege in 1948 was a desperate time for all the inhabitants of Jerusalem. Ismar David recalled having to consider if it was worth going through a neighborhood known to have snipers in order to find a tree rumored to have edible leaves. Nevertheless, these posters, made under the most demanding circumstances, were sophisticated, technically well-executed, often witty, and graphic in the best sense of the word. They had an impact even long after their initial appearance.3Ibid, p. 14. Authors Zelda Popkin (Quiet Street, 1951), Harry Levin (Jerusalem Embattled, 1950), and John Roy Carlson, a pen name of Arthur Derounian, (Cairo to Damascus, 1951) mentioned them in their books. Incidentally, that hand in Haganah poster #2 is a photograph of David’s own.

In the spring of 2022, the Coffee Gallery at 25 Chlenov Street in Tel Aviv pays tribute to the efforts of Ismar David and his colleague Yossi Stern with an exhibition of a collection of these 1948 works.